As opening statements in the murder trial of Robert Telles began last week, the Las Vegas Review-Journal was confronted with a nightmarish question: How does a newspaper cover the trial of a suspect accused of murdering one of its own reporters?

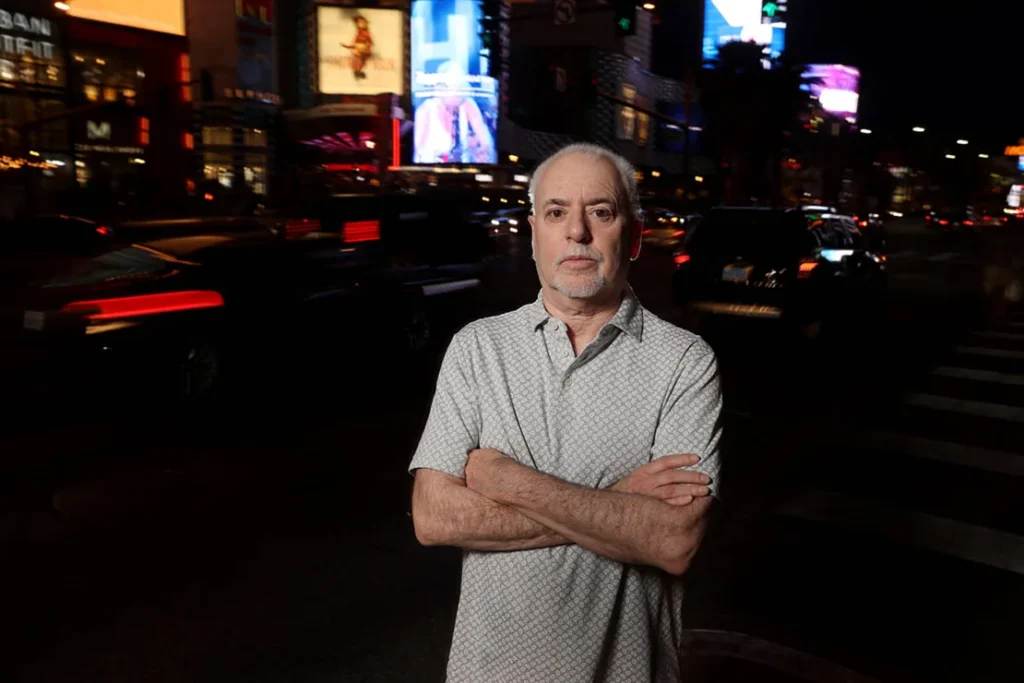

The once-unimaginable prospect is one the newspaper and its staff have faced for nearly two years after Telles, a 47-year-old former Clark County public administrator, was arrested and charged in the fatal stabbing of Review-Journal investigative reporter Jeff German. The shocking death of the veteran journalist came after the reporter spent months covering turmoil and allegations of harassment inside Telles’ office. Telles has proclaimed his innocence and faces the possibility of life in prison if convicted.

Newsrooms are no stranger to tragedy and grief, deploying journalists into war zones, interviewing victims and subjects accused of heinous crimes, and receiving threats to their personal safety. But while most newsrooms face their own discrete challenges, offering objective coverage of a colleague’s murder in a publication’s own backyard is a tall order, even for the most seasoned professionals. Yet for the Review-Journal, this tightrope walk has become the norm over the last two years.

“Jeff’s reporting revealed a boss who was accused of bullying and retaliation, fostering a hostile workplace, and engaging in an inappropriate relationship with a female coworker,” Rhonda Prast, a former Review-Journal editor who managed the investigative team’s ongoing probe following German’s death, said at last year’s Investigative Reporters & Editors’ conference.

In the wake of German’s reporting, Telles went on to lose his Democratic primary race, bringing his time in public office to an end. Following the election, Telles published an angry letter on his website attacking the Review-Journal and its reporting, denying allegations in German’s reporting.

After German’s body was discovered outside of his home, Review-Journal reporters, still shaken by the grisly crime, immediately embarked on a reporting offensive to find his killer and finish his work.

Reporters and editors pored over German’s reporting in hopes of finding who was responsible for the attack. They soon identified a car that had been spotted at the scene of the crime, linking it to Telles, who was later arrested and charged with murder.

“During those first days, the [investigative] team never stopped. We had to locate Jeff’s sources because he had not shared that information,” Prast said. “Some we found through his emails. I found one person in Jeff’s email trash. Briana [Erickson] and Art [Kane] ran down sources and worked from stacks of printed records Jeff had at home.”

Briana Erickson, a former Review-Journal investigative reporter, endeavored to continue what German had started through her own reporting, retracing the chapters of Telles’ life by delving into “a decade of what people described as toxic and harassing behavior, conduct that never raised alarms at the institutions that could have held him accountable,” she told the IRE conference.

The newspaper dug into Telles’ past, obtaining 911 calls from Telles’ ex-wife and surfaced video of him being arrested years before on domestic battery charges.

Amid the Review-Journal’s coverage of German’s murder, the newspaper sought to protect the late reporter’s privacy and sources. During the police investigation, authorities recovered German’s phone, four computers and an external hard drive from his home.

“We absolutely want justice for Jeff. But his many confidential sources for stories MUST be protected,” Keith Moyer, the publisher and editor of the Review-Journal said in a social media post.

While the Nevada Supreme Court upheld a state law shielding reporters from being forced to divulge their sources, the Review-Journal ultimately provided the prosecution, defense attorneys and law enforcement with “the majority of data” from German’s phone in May.

In the week leading up to Telles’ trial, the Review-Journal published several news articles focusing on the trial and German’s career. In pieces penned by investigations editor Arthur Kane and court reporter Katelyn Newberg, the newspaper established German as a fearless investigative journalist capable of deftly navigating organized crime figures in Sin City and dedicated to his work. The Review-Journal also created a “Remembering Jeff German” memorial on its website, which houses all of the reporting about the slain reporter since his death in 2022.

As opening statements in the trial kicked off, the Review-Journal prominently reported the story on the newspaper’s front page and offered a live stream of the trial on its website.

German’s reporting also played a key role in the trial. Telles’ attorney praised the late journalist as a “good reporter” who “would ultimately get to what the truth was,” and suggested others might have wanted him dead. And Telles admitted that he had lied to German when he denied having an inappropriate relationship.

While journalists frequently cover tragedies, the task is even more complicated when the killing is that of a colleague, said Katherine Jacobsen, who oversees the US, Canada, and the Caribbean for the Committee to Protect Journalists.

“But what journalists are really good at, I think, is being able to put on their reporting hats and, for better or worse, process later and report first,” Jacobsen told CNN. “I very much respect the kind of [sober] approach that newsrooms like Las Vegas Review-Journal take […] when covering these kinds of very difficult topics.”

The Review-Journal declined to comment for this story, citing the trial.

“We’ll let our reporting speak for us until then,” said Glenn Cook, the Review-Journal executive editor and senior vice president for news.

While Telles’ fate is set to be decided by a jury, the newspaper’s staff joins a host of other newsrooms forced to cover trauma afflicting their own staff. There have been 14 journalists killed in the US since 1992, most recently a TV reporter who was fatally shot in Florida last year while covering an earlier shooting, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

In recent months, The Wall Street Journal undertook a public pressure campaign to seek the release of reporter Evan Gershkovich, who was wrongfully detained in Russia for 491 days. While Gershkovich sat behind bars, his colleagues back at home kept hope alive, spotlighting his detention on the front page, holding read-a-thons, global runs, and social media storms to draw attention to their colleague’s plight.

In 2018, The Washington Post similarly deployed a reporting offensive during the disappearance and killing of Saudi journalist and contributing columnist Jamal Khashoggi. When Khashoggi was still thought to be missing, the Post published multiple stories detailing the circumstances of the reporter’s disappearance and later played a key role in uncovering the facts around the journalist’s murder.

And as the war between Israel and Hamas continues to rage on, at least nine journalists working for the television network Al Jazeera have been killed in the intense fighting. The Qatar-funded outlet has not shied away from condemning the killing of its reporters and photographers, blaming Israel’s military in sharply worded statements.

Given the nature of the job, journalists are often charged with covering the deaths of their own peers as they would other day-to-day events in their communities, a particularly daunting and emotional task.

“The person who’s most equipped to cover this is the victim – it’s Jeff,” John Katsilometes, a Review-Journal columnist, pointedly said in the wake of German’s death. “He would be the one we turn to on something like this.”